It’s nearing massage time in Tito’s spa. Blue, industrial-sized clocks suspended from the corridor ceiling tick off the minutes at ten meter intervals. On the walls, Tropicana-colored stripes point toward several ominous sounding destinations: “Elektroterapija,” “Zubna Ambulanta,” and “Laboratorija.” As you pad toward the Beauty Center, distant voices hover, a door closes, footsteps fade, and far away the sound of a lone ping– pong game is almost audible. Perhaps long ago, David Lynch traveled to what was then the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and made a film that you’ve just entered. Feelings of nostalgia aroused by the surrounding signs of that socialist-era civilization well up simultaneously with a sinister sense that the experience isn’t vicarious but actual, that somehow you’ve entered the banal reality of that past.

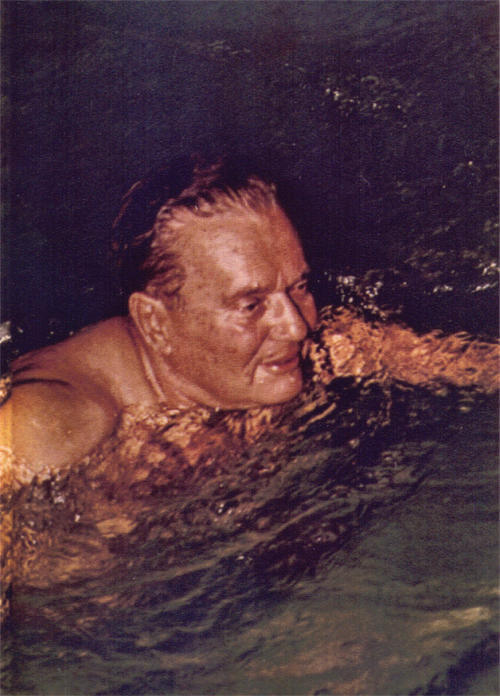

The famous therapeutic properties of Igalo’s Adriatic mud have been drawing crowds to the spa on Montenegro’s Boka Kotorska (Bay of Kotor) for more than a century. Mud, like other, more celebrated substances, encourages people to come together, get relaxed, take off clothing, and heal the wear and tear of everyday life. The seaside suburb of Igalo seems to have passed through the former Yugoslavia’s astonishingly complex and brutal civil war without much trauma; that the Institute has survived since Tito’s era without much change of any sort — from the well-preserved interior decor to the practitioners’ education and the treatments offered — is something of a miracle.

For some reason (the hotel representative with whom I spoke was at a loss as to why), Norwegians have an especially enduring relationship with the health resort, which was built up to its current, new brutalist form in the 1970s. In the decades following Tito’s death, Dutch, German, and, most recently, Russian travelers have discovered this haven of low-cost, qualified thalassotherapy and medical treatments, as well as starched sheets and facials.

Of course, searching for a satisfying spa experience in an institution that channels the Cold War era may seem as counterintuitive as checking into a sprawling, water-stained, concrete bunker to commune with nature and get a little rest. However, in the wake of two world wars, the architectural aesthetic manifested at Igalo apparently offered a logic of exposure that made a lot of sense as a form of civic therapy. The honesty of raw concrete and exposed architectural structures asserts the ultimate in social, political, and cultural transparency — a building-sized X-ray and the first step toward diagnosis and rigorous treatment for a sick society.

The Institute’s architectural-pathological ambitions extend to its clients. Spa therapy is understood first and foremost as a medical, scientific enterprise; the Institute houses a university medical program, and “wellness options” such as facials, pedicures, and massage are relatively new additions. Sitting down to a breakfast of whole-wheat toast, boiled egg, and cucumber, it’s easy to feel that you should be thinking more seriously about your skeletal, respiratory, and muscular systems and investing less in your surfaces.

It may also occur to you that the ethic of unselfish responsibility, integral to the Institute’s original mandate, is precisely the kind of learned behavior that other luxury spas aim to shut down. The “get beautiful” instinct that guides one toward acupressure, pedicures, and facials is discouraged at Igalo. Rather, the State (the Institute is jointly owned by Serbia, Montenegro, and, to a significant extent, its employees) has engineered a supportive environment to help the client monitor and maintain personal well-being — but to what end? The inclusion of a bomb shelter alongside an art gallery, dental facilities, and a store for minor purchases indicates an unpleasant reality that threatens to interfere with your cure.

The government sponsorship of activities aimed at disarming your everyday anxieties also contributes to a diffused sense of paranoia and the alarming feeling that you are enclosed within an early sci-fi experiment. The chandelier shaped like a strand of DNA, the transparent space-bubble telephone booths, and the communal television lounge on each floor — the “this can’t be real” quality of the spa’s interior spaces and decoration certainly adds to the socialist-heyday holiday charm. At night, the reception area, main bar, and restaurant are mostly quiet; light seems to seep out from recessed corners and from where the wall and ceiling meet; a maze of corridors and complex elevator systems feed guests towards the broad horizons typical of the spa’s designated social activity hubs. The almost absolute darkness outside gives the impression that you’re floating through deep space; it’s also possible that you’re on a mission exploring the bottom of the ocean. In either case, cooperation with the crew and performance of duties are very important, and leaving doesn’t seem like an option.

Which is ridiculous, of course. The walls of staggered balconies testify to the fact that you are just one of many identical holiday-goers looking for a bit of sun and a newspaper. In any case, the particular experience that is the Igalo Institute may not last beyond 2007. After thirty years, the spa is enduring capitalist growing pains and is due for private ownership and a full makeover. But for now at least, this monument to the body politic is open for business in all its symbolic and sensual glory, and the flocks of well-sunned elderly ladies and gentlemen in terrycloth don’t seem to be going anywhere.