Shaaban and I have been playing hide-and-seek over the telephone for some time now, he grumbling and me rambling. This is how it goes: Every time I call, I must reintroduce myself, as though we’ve never spoken before. I remind him how I got his number (through a musician contact) and that he has asked me to call back to finalize the specifics of our interview on his iconness. At this point, he usually tells me to call back at a later time, and when I do, his mobile is invariably turned off. After nearly three weeks of playing this game, and just when I’m ready to call it quits, he betrays the faintest glimmer of repentance and uses my name for the first time. Never mind, Uncle Yahia (long pause). Listen, let’s meet on Thursday, at the Rehani Theatre on Emaddeldin Street downtown, 10 pm. That’s it, Professor Shaaban, it’s a date? No more calls? I ask, relieved. He grunts in assent.

To his credit, Shaaban has no delusions about his assets. In a typically candid interview with the Christian Science Monitor in 2002, he offered: “You know, I can’t sing. And look at my face — it’s ugly, really ugly. But for some reason, people keep throwing their money at me… Who am I to say no?” Shooting to fame some five years ago, with his bluntly titled “I Hate Israel,” Shaaban seems to have tapped into the often frustrated and disenfranchised mood of the Egyptian (and Arab) street, singing what the people are saying — or rather, what they are afraid to say. The local governmental and cultural elites, however, have condemned him as boorish and lowbrow. One participant in a 2001 parliamentary debate on his influence on Egyptian society declared, “Shaaban does not represent any artistic or cultural value.” A year later, in an attempt to discourage him from appearing on live television, politicians hinted that singers appearing on state-run channels should at least possess university degrees.

But mean-spirited talk of bans and accusations of vulgarity have only contributed to Shaaban’s burgeoning street credibility, and his refusal to feel shame about his humble origins has gained the respect of many. “Presenters like to make fun of me… but that’s OK… I never expected to eat meat every day,” he confessed to the Monitor. And while his work may lack artistic value, his relevance evidently lies elsewhere. Neither accomplished musician nor teen-age heartthrob, Shaaban is a cultural phenomenon, an improbable popular and populist hero who has considerable sway with the masses.

Disaffected youth hang on his every word and commit his lyrics to memory. One song of a few years back, “I’ll Stop Smoking” (although he hasn’t), is rumored to have been more effective than nationwide anti-smoking campaigns. Shaaban’s is a classic rags-to-riches tale: A lower class, illiterate ironing man (ironing by foot, no less) did unbelievably well for himself, including “appearing on CNN” (as he repeats triumphantly in his one film, Citizen, Detective and Thief — in which he plays a wedding singer). But by just playing himself, Shaaban has secured his position as the voice of a nation of underdogs. For the insulted and the injured, unemployed and underemployed, he is someone they can trust to tell it like it is. In this sense, his rap music is a news flash for the man on the street.

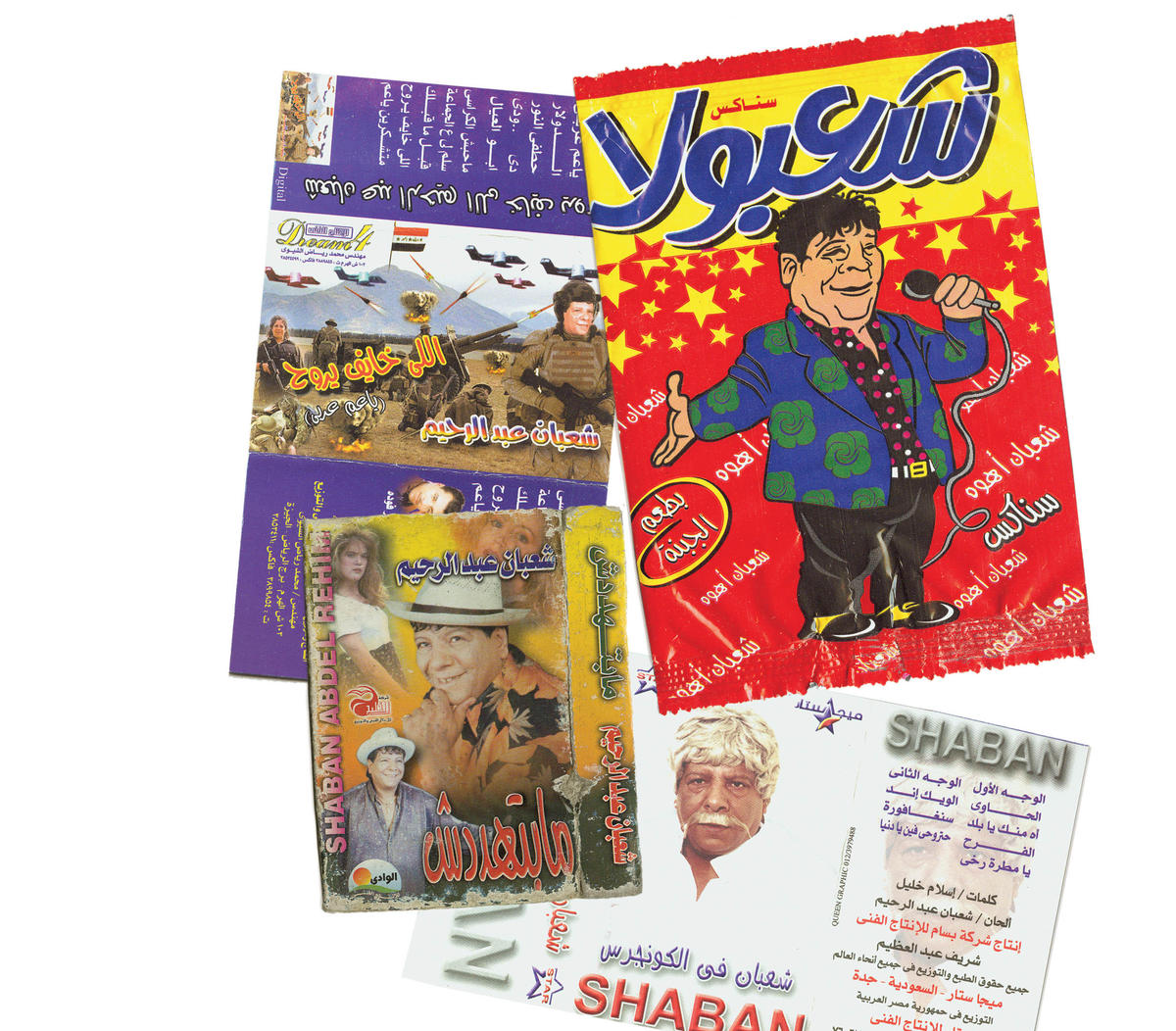

In addition to bestselling albums throughout the Arab world, Shaaban has appeared in TV serials and is currently co-starring in a commercially successful play (in its fourth year). For better or worse, his persona begs for appropriation as a cartoonish icon: The kitsch he’s inspired includes a variety of potato chips bearing his nickname, Shaabolla. Chinese Ramadan lanterns feature his likeness in shiny colored plastic, and his mug greets you on T-shirts worn throughout the Middle East.

Shaaban’s political forays, however, are less amusing. Ill-digested (and often ill-informed) political commentary continued following his infamous Israel ditty, in which he sings that he wants to die a martyr. In the lead-up to the Iraqi invasion, he released a reactionary pro-Saddam song titled “Saddam, I Love You,”and more recently sung an inflammatory pro bin Laden tune (reportedly banned from the market) with the catchy chorus “bin bin bin bin bin Laden.”

Now that Egyptian President Mubarak is up for his fifth term in office, and the people have finally decided that enough is too much (with a protest movement called “Enough,” frequent demonstrations and violence in the streets), Shaaban has made the unpopular decision to endorse him. He shamelessly sings the praises of Mubarak’s achievements over the last twenty-four years in the dubiously titled “The One We Know Is Better Than the One We Don’t”: “And after all this… who should be nominated to run against you?… I’ll say it once more, word of truth, the nation chooses Mubarak.” Consequently, the man once referred to as “the pulse of the street” now faces accusations of hypocrisy from the same fan base that accorded him this title.

The play in which Shaaban appears is titled Do-Re-Me-Green Beans and stars one of Egypt’s best-loved comedians, Samir Ghanem. Since his heyday in the seventies, Ghanem has had a fondness for spastic farce and freakish co-stars: cross-dressers, midgets and mad old men. From the look of the posters outside the dilapidated theater — Ghanem in toupee, oversized shorts, and glittery gold shoes, Shaaban appearing effortlessly like a circus clown — vaudeville is still the order of the day.

I make my way into the smoke-filled cafeteria at 10 pm sharp and am told I must wait a while. The man in the ticket booth tells me that Mr. Shaaban does not show up before 10:30 or 11, since he only comes on during the second act. Yes, but I have an appointment, I interject. Then have a seat, he says with a wily smile. Uneasily, I settle down and prepare myself for a wait, cautiously sipping the complimentary lemonade.

10:30 The audience is tumbling in now, one expectant family after another squeezing through the narrow entrance. At the door they are confidentially propositioned: “Photo with the stars?”

10:45 A very young Gulf Arab couple seated behind me are being casually had. The cafeteria waiter hoarsely whispers into the unassuming man’s ear that he has won a prize. To secure it, he must act now and buy a special ticket. He gets up and buys one.

11:00 Still no sign of “the man of the people.” A bell has gone off signaling the beginning of the play, and the cafeteria is clearing out. An unlikely seduction scene between a coy boy and a gregarious girl is elaborately unraveling. A much younger child screams blue murder. I get up to call The Man.

11:15 Not surprisingly, his mobile is turned off, and I return to my seat; the theater staff regard me now with a mixture of pity and schadenfreude.

11:30 Only a few people remain in the cafeteria: a dejected looking kid (fan?), a restless man with a notebook, eyeing me from time to time with fellow-feeling (journalist?), and a Shaaban look-alike (if such a thing is possible) in a comparatively demure canary yellow shirt and blindingly white shoes. He appears somewhat dim-witted, saying “excuse me” repeatedly to no one in particular. Because of the uncanny resemblance and deferential treatment he receives, I assume he must be family.

11:45 The room is alive with facial tics and the language of anxious fidgeting — my own included.

12:00 One of the ushers winks at me. Shaaban’s driver is here, he confides. Perhaps I should check the changing room at the side of the building. He returns to his post, whistling nonchalantly, and winks again on my way out.

12:15 Illumined by garish green lighting, a man with a scar from his mouth to his ear interrogates me at the changing room entrance. Nah, that was Shaaban’s kid, he eventually volunteers. Shaaban always comes in through the cafeteria. I call Shaaban once more and get through this time. Yes, he’s on his way, a driver answers. Minutes, now. Click.

12:30 Back at the cafeteria, two silver cars pull up and I slowly make my way out, the anticipation having mostly evaporated. Turns out it’s not him, but two more of his drivers. You’re the one who spoke to us on the phone? one of them asks accusingly, narrowing his good eye. Yeah, I sigh. I’ve been waiting for two and half hours now, we had an appointment… Never mind, listen, he’ll be coming any minute now, up this side street, wait here with me… On the lapel of the chauffeur’s checkered shirt, I notice an image of Shaaban stitched in gold thread. The man wears shiny red shoes not unlike his employer’s.

1:00 In the midst of intermission mayhem, the Big Man arrives in a glitzy SUV with a sizeable poster of Mubarak in the windshield, trailing people and commotion. My first impression as I catch sight of Shaaban stepping out of the vehicle, puffed out like a blowfish, is one of unexpected toughness. It’s difficult to square the prankish persona in the posters with this unsympathetic creature and his small unsmiling eyes. Sure, he looks like himself — preposterously greasy hair and wide waistband — but he feels different. The animating spirit peering out from these eyes is armored, hard.

At the entrance of the theater he stops for a long handshake with a monakkabba (woman veiled to the eyebrows in black, with gloves on). Soberly dressed in a dark suit and pants, Shaaban moves very slowly and somehow gives the impression of reptilian dry and amphibious slick at the same time. Kids and cops clamor around him as he is ushered into a side room off the cafeteria. He’ll see you afterwards when the people have cleared out, his chauffeur assures me. You couldn’t possibly have a conversation in the middle of this madness.

1:15 When the audience have returned to their seats The Godfather emerges from the inner chamber and sits down for a glass of tea, thronged by a tight ring of his henchmen, including scar-face. I catch Shaaban’s eyes from across the room, suspiciously scanning me as his driver motions discreetly in my direction. He lingers for one long joyless moment, and then sends one-eye back to me, apologizing profusely. We’ll have to do it another time; The Man is expected on stage in minutes. Before I can process this information, Shaaban has left the building.