The sheer genius of the plastic ice-cube tray first arrived on Iranian shores with President Harry Truman’s broad-ranging Point IV program and its emphasis on “the underprivileged persons of the Earth.” Later, American companies like General Electric and the York Corporation would provide the stuff of suburban fantasy, in the form of shiny kitchen utensils, to Iranian kitchens. High school textbooks on housekeeping lifted most of their copy from magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal and Good Housekeeping. And by the late 1950s, the McGraw-Edison Company’s Air Comfort Division in Albion, Michigan, was helping Iranian cities stay cool thanks to their iconic air- conditioning units, especially when the country’s famously scorching summer heat waves rolled in.

Some years later, an Iranian company called Arj began to produce a local version of McGraw-Edison’s air coolers. Arj, which means “value” in Farsi, set up a sprawling joint Iranian-American factory on the old Karaj Road, on the outskirts of Tehran, devoted to electrical equipment and appliances. Among the many items produced by Arj was a clunky blue and white metal air-conditioning unit known as the Kooler. Its affordability and perfectly acceptable quality made it a hit among a certain kind of middle-class Iranian.

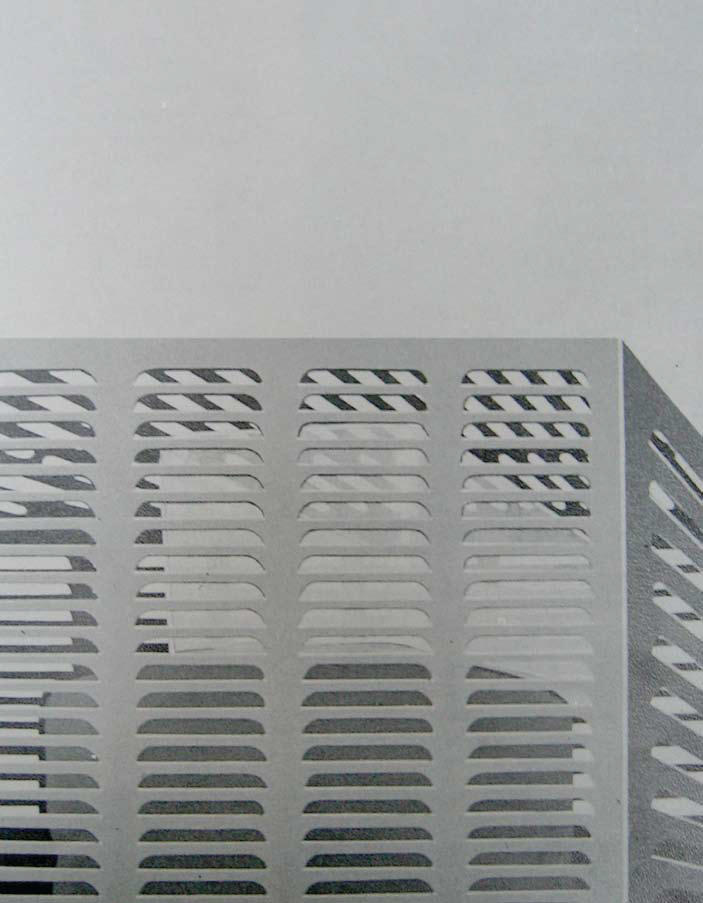

The Kooler and other later brands (eg, Absal and Arj) were not the typical window-mounted machines used in the States. Rather, the Kooler stood apart from the building, either propped atop a balcony like a tiny industrial minaret or attached to a metal frame. These boxes “decorated” countless facades around cities, resembling stalled elevators or awkward miniature tree houses.

In the late 60s, these air coolers captured the imagination of an Iranian artist named Mehdi Husseini, previously known for his reliably abstract oil paintings. At the same time, a fellow artist named Behjat Sadr began riffing on imported Venetian blinds as objects of art, while Coca-Cola bottles served as inspiration for Parvaneh Etemadi. Indeed, everyday commodities inspired a generation of Iranian artists, many of them educated in the West, and many perhaps not wholly unaware of a man named Andy Warhol silk-screening soup cans somewhere across the ocean. Most of the objects that figured into these artworks were either imported or joint Iranian-Western products. (In a strange twist, jointly produced industrial products were called “montage.”) Under the shah, the apple of the American eye, Iran became a repository for all manner of mass-produced consumer detritus. By the second half of the 1970s, on the verge of the revolution, the Iranian market was completely overwhelmed by iconic American products, from Kentucky Fried Chicken to Westinghouse; the value of US exports to Iran hovered around $326 million.

Plainly, the reality of this Westoxification — to use a term popular at the time — raised the ire of leftists. But so did the Warholian art of the era (and, it should be said, Warhol’s art itself). The Marxist art critic Khosrow Golsorkhi once proclaimed that such works turned aesthetic value into exchange value. The postrevolutionary elite condemned such pop works, too. Artists were barred from displaying their “capitalistic works” in local museums due to the mobtazal character of their art — a term implying both corruption and kitsch. Even commercial advertisement in local media was forbidden for almost a decade, while Islamic revolutionaries drew a sharp distinction between local and imported goods, a view that defined the essence of household objects. Terms such as halal vs haram (accepted vs forbidden by God) and taharat and najasat (purity and filth) — once applied mainly to the human body and its environment — now extended to imported commodities. Montage was considered haram, as described in early postrevolutionary texts like Hasan Tavanayan Fard’s Karkhanijat-i Montage: Iqtisad-i Shirk (Montage Factories: The Sinful Economy).

It is nearly thirty years since students took to the streets and shouted “Death to America” at the gates of the American Embassy, and while the popular consensus against the excesses of the West seems to have faded (there are more BMW and luxury-watch ads along Tehran’s highways than ever), the regime continues to pay lip service to the purported evils of Western consumerism and its associated blight. In what was once sleepy Karaj, the Arj Company factory and its patrons are all gone, replaced by a growing number of factories owned by the regime and its cronies. As for the Kooler, it lives on, its exceptional profile and color becoming a standard prototype for all subsequent locally produced varieties. Occasionally, one of the vintage originals can be spotted perched atop a building, its exterior caked in the dust that marks Iran’s bigger cities. Behind their dull facades, these boxes tell forgotten stories about an earlier time, of coolerators and kings, back when America reigned supreme.