He ate camp and shat punk, his style a fizzing intestine stuffed with culture’s slime and scraps. “I’m sort of like a receiver,” he announced, months before he died.[1] Death itself transfixed him, especially his own. He left us an art of psychosis and cruelty, wit and filth, an art whose force and ballistic extremity arrived at a startling grace. That grace expressed an ethics — a way to think, and be. When a critic asked about his politics he replied, “I believe that one has to not be a victim.” Be ghastly and catastrophic, get blown up or mowed down — the moving final lesson of his roving, shocking life. In an age of fear and crisis, he wrote plays about broken people: how they’re made brittle, vacuous, flat, and weak by the lords and ladies in media and the state — that glittering, elaborate architecture that Marx called the “inverted world.”

Invert, an old word for what Reza Abdoh was. His death from AIDS in 1995 cut short his rule as the Robespierre of American theater. But the disease fed him as it destroyed him, eliciting his fabulous wrath. Interviews bring him back to us in all his queenliness and mystique. He could be irritable and distant. He also liked to lie. He scoffed at the “avant-garde” but spoke in swiveling evasions and billowing decrees. Theory largely bored him, as did the word “radical,” because “what’s radical is in the streets, the war in Iraq is radical.”[2] He thought that actors didn’t have to be intellectuals, unless, of course, they were, in which case they should submit their minds to the extravagant discipline required by his work: “You need to have a certain haircut, you need to have a certain walk, you need to have a certain voice, you need to have a certain relationship to the text, and you need to basically convey a certain set of emotional, intellectual, and physical connections to the audience so that the relationship is complete, because otherwise you’re not communicating anything.”[3]

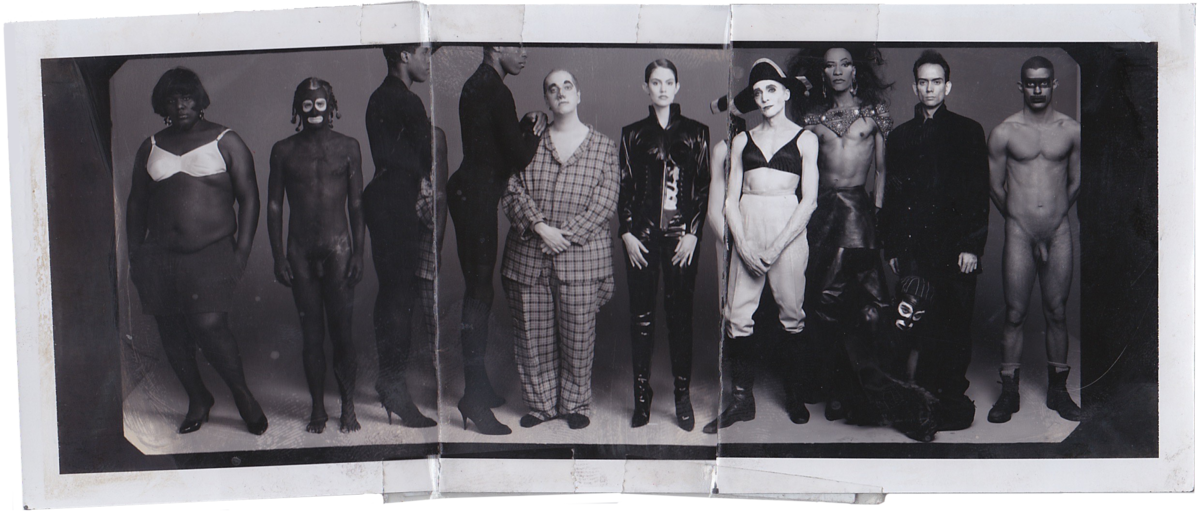

Voilà the valiant Artist, with his ardor and rigor and totalitarian reputation — but surely we’ve met him before? This is the male homosexual maestro, scowling amid a microcosm of loyal personae, all locked in rigid orbit around his tyrannical hauteur. Comparisons flash to mind: Warhol and his Factory; Fassbinder and his friends. Abdoh had dar a luz, the company he founded in 1991, whose bodies and voices supplied the material for his productions. And just as Warhol was drawn to advertising and Fassbinder to melodrama, Abdoh, too, poured his intelligence into a vessel of polished pop: the blank, shredded syntax of exploitation film and cable TV.

Bombs over Sarajevo, murder on the nightly news, the blooming urban crises of AIDS and gangs and crack: this was the malignant logic of Abdoh’s time and place. He was a foreigner and a dissident armed with rage and militant will, a will strengthened — bitterly nourished — by the experience of loss. He was born in Tehran in 1963 to a brutal, prosperous patriarch and his yielding, gentle wife. Young Reza was painted neatly into this repressive tableau. Then came protests and insurrections; in advance of the Iranian Revolution, the Abdoh men, nearly penniless, escaped to the community of Persians that had sprung up in Los Angeles.

Reza revolted. He wrote poems, made videos, turned tricks, dropped out. He plunged into LA’s gleaming demimonde, a realm stuck with shards of showbiz but mostly raving in Hollywood’s shadow. From an astonishing precocity came Abdoh’s first plays, then videos, then massive multimedia productions like Minamata (1989), Bogeyman (1990), and The Hip-Hop Waltz of Eurydice (1991). Here was a new sensibility, one that swung from shrieking to somber, from crashing to blue, unrolled from a consciousness forced to face its own decline. He’d been diagnosed with HIV in 1988 and saw his failing body as a token of a blasted world: walls toppling, history closing, a rabid right-wing puritanism throbbing fiercely with new life. “In my work,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1990, “there are moments of complete mayhem, unforgiving and relentless violence, passions that are like excrement. It’s not because I’m cynical.”[4]

Abdoh wasn’t cynical, but I do see him as a kind of Cynic — as the rightful heir to those Greek philosophers who renounced luxury in the quest for virtue. The most notorious among them was Diogenes of Sinope, a kind of bohemian exile, blurred for posterity by conflicting accounts. Born wealthy in Asia Minor, he fled to Athens, slept outdoors, was sold into slavery, practiced philosophy, and was remembered by his contemporaries as filthy, lecherous, impudent, glib, prone to cackling contraventions of cherished social mores — Plato dubbed him “a Socrates gone mad.” Diogenes strove to “deface the currency,” to leave his insolent stamp on custom and language, whatever streamed through the polis and gave it life and shape. He gleefully exposed his most intimate acts: pleasuring himself in public, stuffing his face in the market, sleeping in a massive tub that he carted peevishly through the city’s streets. Philosophy, for Diogenes, was a way of life and a physical trial, to be stripped of its intricate “discourse” and practiced in the flesh. “Cynic” comes from kynikos — meaning “like a dog” — which is what crowds, revelers, and children shouted at him as he went trundling through the square. He called himself a hound of heaven.

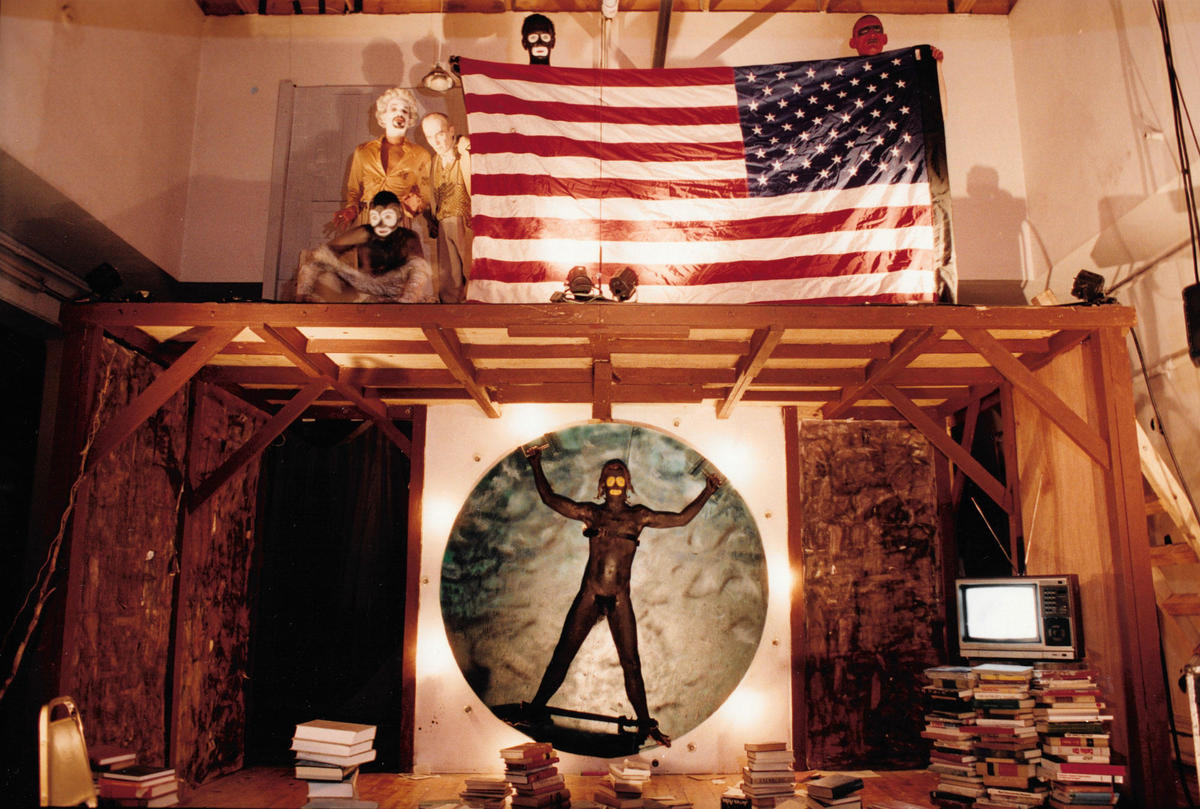

Violence blazed a path through Abdoh’s last productions. He liked to speak of “the excoriation of the body” — which is one way of describing how his plays humiliated the human form. The Law of Remains (1991) follows Andy Warhol as he makes a film about Jeffrey Dahmer, the rapist who killed and feasted on dark-skinned boys. Quotations from a Ruined City (1994), Abdoh’s last play, is grand and dolorous in its pacing even as it addresses genocide, torture, illness, and civil war. But the production that was the most bizarre in its cruelty, the most egregious in its barbarism, and the most Cynical in its fusion of crudeness and political insult, was a play that premiered in 1993. He called it Tight Right White.

Is it ironic that Abdoh gave this tinkling title to a work so howling and depraved? Perhaps — but the play’s fracture and profusion make “irony” seem quaint. Irony flits from text to subtext, from world to veiled underworld. Abdoh, with savage ecstasy, drives us irretrievably into Hell.

Behold Hell’s chatty denizens — liars and cheaters, strivers and pigs — who stomp through two hours of voluptuous disjunction. The speech is loud, the movements fast, the action brazen in its refusal to cohere. Tight Right White heeds the vanguard impulse to slash and mangle form, and that taste for violation extends to the human physique. Rape, lynching, gunshots, whippings, the shivering injection of heroin onstage: Abdoh’s “plot” struts forth with brutish relish. This is a play about race and sex — that is, about the way of all flesh, how it’s beaten, fondled, mutilated, shaved.

And then slathered with liters of glistening paint. Tight Right White is based on Mandingo (1975), a film made from a novel about a black American slave. The genre is blaxploitation. The movie clings madly to the fantasy of the black phallus, with its dangers and pleasures and marvelous power. But Abdoh’s version splices the Mandingo story, which unfolds on a plantation in the Deep South, and the meeting of the Jewish TV producer Moishe Pipik and a figure named Blaster. The latter is black; Pipik desires him. Pipik himself moves freely between the two realms, traipsing from antebellum artifice to the dingy present. White people twirl in blackface, black actors are painted white, and Pipik wears a massive, strap-on hooked nose in this risky little exorcism of appalling cliché.

At the play’s start, Pipik says he’s on the hunt for gripping stories. He’ll repeat this several times. He sees Blaster — black, male, addicted, abused — as a diamond in the rough:

MOISHE PIPIK: You know Blaster we are looking for that gem of a tale to tell on TV. You wanna be on TV Blaster?

BLASTER: Yeh.

MOISHE PIPIK: How come you jump on people like that?

BLASTER: Everybody want to have things.

MOSIHE PIPIK: Other ways to have things.

BLASTER: Fast buck, Ima go for it. I tried working. Work here for six hours make around twenty dollars a day. If I can make twenty dollars a minute what I’m gonna go for?

The lines fly across the stage with smashing velocity. But they take a familiar shape: on one side, wit and savvy; on the other, savage need. Between the Jew and the Black runs a ribbon of vexed recognition and mutual mistrust. Like Prospero and Caliban, they’re twinned figures of exile and abjection, each pitched at a bitter angle to the white American norm. But Pipik wields power, whereas Blaster has none; Pipik makes jokes, while Blaster shrieks. And Pipik works in television: he’s the gloating gatekeeper to a world of lurid spectacle, which makes meaning and money from Blaster’s black pain.

“MANDINGO!” A voice shouts; the scene changes. Instantly we find ourselves in the American South. A slave trader is haggling with a young plantation master who’s trying to sell him live human flesh. Again, the words are harsh and fast; voices exit bodies in brute stripes of sound. Pipik returns and shares his wisdom about the schvartzes — “You can’t eat ‘em and you can’t plow ‘em under” — but the action has spun away from him. We’re in the lugubrious universe of chattel and masters, masters and mistresses, a semiotic scramble of power and hunger. Hammond and William Maxwell are the proud white patriarchs; Big Pearl, the hollering mammy. Then there’s Blanche (I’ll let you guess her race) and the slaves Mead, Agamemnon, Lucretia, and Ellen — twitching, twirling ciphers in this circus of human suffering.

“Artaud You So,” ran the headline of the review in the Village Voice. The tone was one of sneering fatigue. For all the mind-shredding delirium, the critic Michael Feingold felt sure enough of the play’s point to plop it presumptuously in his first paragraph: “Tight Right White is a piece of intense and revolting accomplishment, executed with enormous skill, that assaults audiences with a near-two-hour barrage of obscenely racist images, for purgative purposes: a psychological enema, shoved up the id of liberal theatergoers to expel the unhealthy imprints a racist society has deposited there.”

If only. But Tight Right White is more than a psychic purge. It crosses punitive caricature with genuine pleasure, outrageous provocation with rippling catharsis. This is accomplished mostly through music: the two-hour production is pricked and ventilated by pop, rap, soul, and disco. What emerges is not merely Artaudian hostility or a string of drubbing stimuli but a cognitive experience sliced through by contradictions. This is no cleansing by Abdoh of his audience’s muddy souls; Tight Right White depicts a world so enclosed by the spectacle, so married to its cruelties, so invested in its lies and asphyxiating myths, that flight from the system is basically unthinkable. In a world of malevolent, multiple messages, Abdoh’s path is the Cynical one: he must deface the currency.

Hence the use of black American music — songs by Nina Simone, Curtis Mayfield, and Redman, among others, rolling over the blackface and whiteface, the ballet-dancing Klansmen and flashing video monitors. “You make me feel miii-iiighty real,” Sylvester sings, and that realness serves as a kind of sensuous lure. There is no burrowing down to the bottom of the spectacle; this is a spectacle about spectacle, a tantalizing exploitation of our appetites and senses. The world of slavery melts into the world of TV. “Sell us your death!” the characters scream at Blaster in the play’s final scene. He is a canceled psyche, his blackness a malign metaphor for the pain of identity itself:

MOISHE PIPIK: Who are you?

BLASTER: Blaster.

MOISHE PIPIK: Who are you running from Blaster?

BLASTER: FBI.

MOISHE PIPIK: You rich?

BLASTER: I don’t know.

MOISHE PIPIK: You poor?

BLASTER: I don’t know.

MOISHE PIPIK: You clean?

BLASTER: I don’t know.

MOISHE PIPIK: You smell?

BLASTER: I don’t know.

To which a contemporary critic can only sigh, and say — so much of Tight Right White is impossible to justify. Its gestures violate the standards of our day, and of Abdoh’s. Whether intended as metaphor or as gimmick or as theory of pop, there’s no satirical inflection or grandiloquent irony that can contain or nullify the force of blackface. Or so we say. I have never seen Tight Right White, and never will. The work is not in circulation, it cannot deface the currency; I feel locked out of my own feelings because AIDS took Abdoh away. There are scripts and bleary videos of Tight Right White, yes, but they muffle the blast of the thing they seek to save. The hunger and hurt of this dead man’s play lie at an elaborate remove, now, from who and what I am — my bouquet of identities and tastes — but whatever that is owes something to what he did. He can madden and offend me, transfix and perplex me. But he eludes me.

MOISHE PIPIK: Who are you?

BLASTER: I do my work, pack my bag, and leave. I’m a queer prophet.

[1]: Quoted in Philippa Wehle, “Reza Abdoh and Tight Right White,” in Reza Abdoh, ed. Daniel Mufson (Baltimore, 1999), p. 32.

[2]: Quoted in Howard Ross Patlis, “Dark Shadows and Light Forces,” in Reza Abdoh, ed. Daniel Mufson (Baltimore, 1999), p. 29.

[3]: Quoted in Josette Féral, “Theatre is Not about Theory: A Conversation with Reza Abdoh” in Reza Abdoh, ed. Daniel Mufson (Baltimore, 1999), pp. 18–19.

[4]: Richard Stayton, “Impresario of the Avant-Garde,” Los Angeles Times, December 23, 1990.