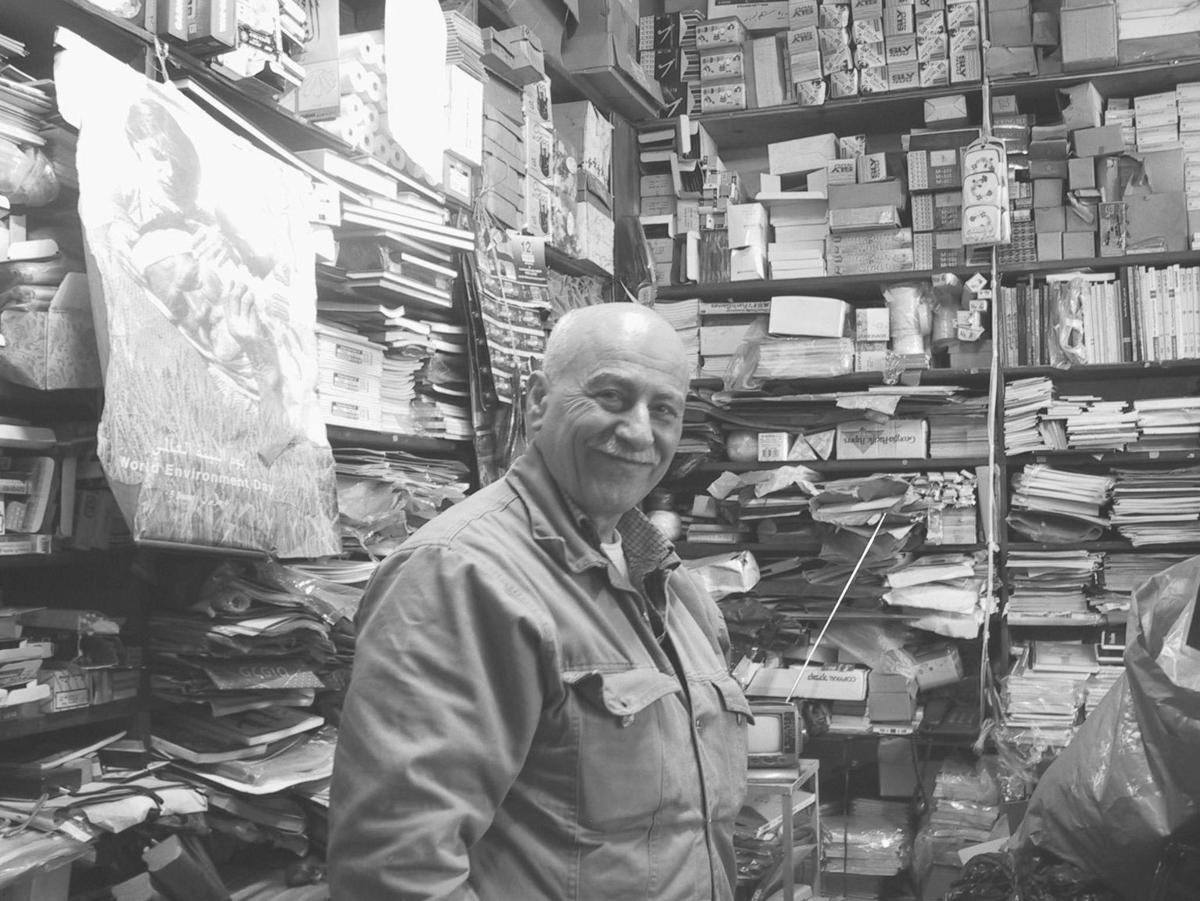

The following is an excerpt from a 2005 interview between John C Welchman and Los Angeles–based American artist Mike Kelley. The interview introduces a volume of interviews edited by Welchman entitled Mike Kelly: Interviews, Conversations and Chit-Chat (1986–2004), published by JRP Ringier, Zurich & Les Presses Du Réel.

Born in Detroit in 1954, Mike Kelley is one of the most influential artists of his generation. While attending the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, he co-founded a band called Destroy All Monsters that used nonmusical instruments like vacuum cleaners and squeeze toys to make music. After graduating in 1976 with a BFA, Kelley moved to Los Angeles to attend the California Institute of the Arts. Kelley did his first public performances that year in Los Angeles, using many of the sculptural works he was making at school as props. In 1978, he gave up painting. His graduate thesis show consisted of a collection of plywood birdhouses.

Kelley’s works provoke, but never just for the sake of it. His preoccupations span desire, pop culture, the juvenile, sociopathology and kitsch. Among other things, he has negotiated music, video, performance, writing and even curation. In 1982, he made his first work in video, The Banana Man, featuring a character indirectly derived from the children’s television show Captain Kangaroo. In the late 1980s, he began creating stuffed-animal works from toys and handmade natty afghans purchased at thrift shops. He made his Garbage Drawings, based on the Sad Sack comics, in 1988. In 1993, the artist curated The Uncanny, an exhibition of unusual interpretations of the body. His last major exhibition was Day is Done in 2005 at Gagosian Gallery in New York City. Drawing on common American tropes — from school plays, Halloween or dress-up day at work — Kelley covered the cavernous Chelsea space in a quasi-religious, apocalyptic freak-show pageant of photographs, dolls, music videos, horror films and props. While his immediate concern seems a contemporary American culture that is irrational, dark, pointless, Kelley’s work transcends context — finally enlightening us as to the performative nature of ritual in your culture, my culture, any culture. Either way, it’s all very bizarre, while Kelley seems one of the last artists to defy the confines of the neat, digestible, reductive art that increasingly populates our surrounds.

John C. Welchman: OK Mike, we’ve got copies of the interviews here, 12 conversations with a whole range of people going back to 1986, when you talked with Michael Smith, through to this latest interview with Jeffery Sconce on the Uncanny show in 2004. Tell me something, first, about what the interview process means to you. Most of these are conversations in which you take the lead as the interviewer and you’re mostly foregrounding various aspects of the diverse work of these other people. What does that feel like,being out in front, as it were? And how has that experience evolved for you over the last decade or so?

Mike Kelley: Actually the collection isn’t as uniform as that. There are a lot of different situations here, ranging from interviews in which I wanted to talk to someone to get more information about them, to situations in which I was paired-up with somebody, like Richard Prince, just so that our two names were together—very Interview magazine style. It was the same with the John Waters talk. On the other hand, there are several interviews I was asked to conduct because I knew the artists very well, Jim Shaw and Tony Oursler, obviously, and to interview them in depth for a monograph. And then there are things I was asked to do with people I didn’t know so well …maybe an editor thought I would have an interesting point of view…

JW: People you didn’t know, like…

MK: Larry Clark. Or at least I didn’t know him well at the time. So there’s actually quite a variety of relationships here between me and the interviewee. In most cases I was approached by a publication or institution to do the interview, it wasn’t my idea.

JW: We’ve talked about this a little bit, here and there,but you’ve had a fairly diffident relation to the interviews and their process, right, viewing some of them as a bit throwaway?

MK: Some of them are throwaway, and they’re designed to be throwaway. That was the aesthetic. The Harmony Korine, John Waters, Richard Prince, and Kim Gordon were done for very light kinds of magazines, pop publications that didn’t want anything heavy… in fact they didn’t want us to talk about anything really. They just wanted patter, chitchat, something hip. And of course I’m not so interested in these, but, you know, they’re in the book. Whatever.

JW: How do you feel about the intimacy forced on you by the interview situation, where you sit with someone face to face and effectively cut out the rest of the world. I’m sometimes struck by the strangeness of switching the tape recorder on and trying to bracket out all noises from elsewhere. This seems to produce either a kind of intensity, or, sometimes, even a kind of embarrassment. But it puts you in the way of another kind of knowledge; the kind we use to write when we write, or that we use when we make art or music, or whatever it is. Can you talk a little bit about that?

MK: I know what you mean. But most of these interviews aren’t those kinds of interviews, where you sit down and really get in to depth and let it go where it goes. Most of them had a point or a purpose, mandated by the publication. They had limitations, sometimes severe, on the number of pages, or they had a specific job to do — the Shaw and the Oursler had to range over the artists’ careers. So I couldn’t talk too much about one thing, and we couldn’t go too far. I could do a whole book with Tony Oursler or Jim Shaw, for example, discussing all of our ideas and interests and endless overlaps and disagreements. And I’d like to do something like that, but that’s not what any of these are, really. For the most part these interviews were done for a specific reason. Maybe the most open interview here is the Jutta Koether, which really had no point or objective. I did it simply to have a conversation with Jutta because in the German context she hadn’t really been given much voice, except through her own writings. So the magazine wanted somebody from outside of the Cologne art scene like me to interview her. They could have asked Albert Oehlen do it, but I suppose they thought that the Cologne scene was too incestuous or something.

JW: OK, we’re talking about the nature of interviewing, in an interview, and I’m reaching for this substrate within the interview format that gets close to its center of gravity. And you’re saying that you understand what that is, but that there’s a real sense in which a lot of the interviews here, a couple excepted, don’t really have it. Is it possible to speculate on what this thing is, this peculiar specificity, in the abstract? I mean, what are it’s possibilities and do they really exist?

MK: Sure, it’s what you get in a great conversation. But unfortunately, I think a lot of these interviews reveal the limitations of the art press. You’re never given enough time to go into depth, or you’re given instructions to cover somebody’s entire output, which is impossible. You can’t get into, say, the beauty of all the poetic details of one specific work of art. I could do a whole book with Jim Shaw about one drawing, talking about all the influences and all the aesthetic history that informed it or that it suggested. In fact, that’s what you never get to do in writing unless you write something yourself, because you’re always trying to convey to somebody something that’s very complex, and you have to make it simple.

JW: Perhaps what we’re skirting around here relates to what Roland Barthes called the “grain” of something, that intimate texture that you encounter when you look at something really hard or when you talk about, or hear, it really deeply, rub up against it…

MK: Or when you read a great piece of writing about thinking something through, really thinking it through,as in a great piece of philosophical or critical analysis.

JW: Going back over this list of interviews, and bearing in mind the deeper notion of the interview, this Platonic form that puts us in the shadow of True Discussion, are there any places, any things, any topics that you wish you’d have really rubbed up against with some of these people …but didn’t have the chance? In other words, I guess I’m asking you about the imaginary of your missed opportunities in this volume, the spaces between your exchanges. There’s a sense in which a lot of your recent work is about cathecting new genres of representation through memorial spaces—the blanks and leftovers between space, memory, and perception.So my question: what are some of the blanks and leftovers that you might want to fill in here?

MK: I hate to bring his name up because it’s so omnipresent, but I love Andy Warhol’s novel A: A Novel (taped 1965; published 1968). What I didn’t like about Interview magazine was that it was purposely about nothing. They’d get two people together who didn’t know each other well and they would blather on. Maybe certain things are revealed by this. But what’s great about A — the transcription of a whole day in the life of factory superstar Ondine — is that you really get to understand how this person thinks… without any talk about big ideas. I think that’s what an extended or really good interview or discussion can get to. The things we have in front of us are more about professionalism. It’s like, OK, I’m given a limitation, how do I deal with this limitation? The Kim Gordon conversation, for example, is specifically about that. It’s not a great interview. But it was not designed to be a great interview. It was designed for a tiny little zine. I was given these parameters. I have to deal with the restrictions aesthetically. It’s an exercise. OK, a little pop interview is appropriate because it fits the zine-like nature of Fama & Fortuna Bulletin, which are little artist’s books, a little giveaway. But I can’t do that with a Michael Smith interview for High Performance, or a Larry Clark interview for Flash Art. In these cases I have a job to do: to get across something about their work and communicate some notion of why it was important at the time to talk about it. I have to address major issues.

JW: There’s something a little perverse here though, because, if I’m hearing you correctly, conversation and exchange between people sitting in their own enclosed space — something you might think would be very informal — is governed in the art world by a very restrictive paradigm. The dialogue is commissioned, and you’re asked — almost forced — to do it. You have this many words and such and such an obligation to cover key aspects of a career. It’s almost like saying that you, as an artist,could only work by commission,that you could only do portraits, or whatever …and that would be anathema to you — and to most artists, for that matter.

MK: I have never been given the freedom to do a book the way I’ve wanted to do it. Never. I have never been given carte blanche to do something the way I really wanted to. There’s always an institutional limitation on it in some way or another. Always a page restriction, a money restriction… always something. Only in my own artwork do I have such freedom. Take the Poetics Project, for example. Tony Oursler and I did a series of almost endless interviews with art/music crossover artists and there were no limitations, but there’s also no distribution for it. The discussions have never been printed or circulated.

JW: But you’ve done a couple of projects like this, right? You did the…

MK: Cross Gender/Cross Genre. There’s been no interest in publishing that, either.

JW: Tell me a little bit about that project, because my next question is: how has the nature of the interview situation played in and across your work in general? I think it has traversed it in many ways. Even in your early drawing-like paintings, there’s a sense in which the different regimes of text are dialogues. They’re dialogues of different voices that come sometimes from you, sometimes from others,and are sometimes caught somewhere between the two.There’s clearly a dialogic component here. And your performance pieces, while organized around the concept of the monologue, also, I think, took on a kind of internal self-interviewing process. You did several tape loops in dialogue form as part of the Arena series and associated works. And there are numerous other examples.

MK: The performances were fractured monologues. I always thought of them as being somewhat dialectical, dialectics through dramatic dialogue — false dialogue: monologues randomly split into voices. All novelistic writing is essentially done like this. It’s false dialogue. It’s one author trying to pretend they’re composed of multiple voices. And basically, that’s what I do. I try to make it more apparent by getting rid of the pretense that they’re different voices. And I think that’s something that was endemic to the new novel in the 1960s, and in Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers (1943) with all those characters—but everyone knows it’s Genet fantasizing. He doesn’t try to hide it, and I think I come from that way of thinking. Now dealing with other people, of course… that’s different.

JW: What is the difference for you between the compromised circumstances that you’ve just described, with you being asked by a magazine or whatever to interview another artist, and the reverse situation in which someone interviews you about your own work? You’ve obviously done dozens, hundreds even, of these other interviews. Is there essentially a mindset difference that you take to these encounters?

MK: Well, when somebody comes to you, they have some goal in mind, something they want. And so you either have to stick to that or you have to fight against it. Of course, when you’re being interviewed by somebody you have to keep that in mind: is it OK that I’m limiting myself to their set of questions? This is especially a problem when filmed interviewees are talking about their own interests. You end up pontificating about subjects… when really somebody’s asking you things, but hiding their questions. In a text the situation is clearer, and you can see what’s going on. You can tell somebody is asking questions and their authorship is apparent. But in film interviews, editors often take pains to hide the set-up. I really dislike that. I always think interviewers should be present in film interviews so their subjectivity is present. Yet in ninety-nine percent of film interviews they’re hidden. The idea of history is generally about an abstraction, of trying to take something very complex or individuated — mass individuation — and turn it into a standard. What’s the standard idea of this complexity… when, of course, it’s only interesting if you actually hear the peculiarities of the individual voice? Abstraction is interesting at the level of the idea and a great thinker can get you involved in generalizations and broad concepts. But there’s also something fascinating about this individuation, its specificity. Like you might tape an exchange with a mentally handicapped person and learn a lot about their social milieu that’s extremely informative …even though they’re not great thinkers. This is the kind of thing an interview can give you. The kind of information that you don’t think is important can reveal a lot of things that are culturally repressed — or culturally unconscious, as you say — and that’s very useful information.

JW: It’s like a kind of double thinking that leads to double writing, I guess, because you’ve got two thoughts, two people and then two writings of those thoughts. It’s a spiral, like a little strand of DNA. I suppose some of the best interviews are going to be extraordinarily revelatory in that vein. Though frankly — this is another question to you — I sometimes find that most interviews don’t manage to do this.

MK: No, they don’t.

JW: Do you have any thoughts about who the great interviewers were? You mentioned Warhol… I think one pole is a sort of deadpan rascal who almost inadvertently speaks, or precipitates, social truth.

MK: Well, he had a particular approach, which was to force the person to pose until their shields broke down, often out of sheer boredom,and they just start to go off. They start to talk and then inevitably reveal themselves in some way or another. Or, at least, they reveal their defense mechanisms. I don’t know. The great documentary filmmakers are very good at this. I’m trying to think of a good example… in a very in-your-face kind of way Michael Moore is good at this… though he works more confrontationally.

JW: Well, he forces responses out of normally quiet corporations by embarrassing, by bringing the media and the camera into their lobbies and atriums so they can’t possibly throw him out on his ass… and if they do, he’s already got a lot of what he wanted.

MK: He forces professional people to speak about things they don’t want to. But he manipulates response. Of course, you’re only going to get a certain kind of reaction in this situation, and he knows that. It’s always an embarrassed response, something that reveals that these people are phonies. That’s his whole point. That’s what he does.

JW: That’s very televisual though. Do you think there’s a way that written interviews can precipitate this kind of social embarrassment? I’m not sure… maybe there is?

MK: Sure, yes. I do. I’m trying to think of a good example.

JW: I mean obviously it’s much easier on camera, because it’s all about expression, it’s about gesture, it’s about the fear of the camera and all that can act as a pantomime of social self-revelation.

MK: There are also people who are very good at interviewing and at the same time hiding their intentions and their interviewees look foolish. There’s a whole tradition of this.

JW: Yeah, probably on the radio. Probably in an earlier era than the one that we grew up with, right? It’s really more the 1940s and 50s.

MK: That’s what the right media is really good at these days. Bill O’Reilly, for example, is really good at getting people on air and keeping the questions so limited that they can’t really respond and making them look foolish. This is a very typical right wing strategy.

JW: And Bill Maher on the other side is also very adept at doing it. He actually is able to do it through a certain kind of… I would call it false generosity to the right because he invites the right in but he’s got a sharp enough wit that he can deconstruct them pretty easily.

MK: These are people who have an ax to grind. They’re not really interviewing people. They’re trying to get them to reveal something they don’t want to reveal and it’s all indebted to a particular, preexisting, point of view. I’ve long been a fan of the “wandering” style of documentary, as in the earlier work of the Maysles brothers (Albert and David). Salesman (1969) follows booksellers, bible salesmen, as they go on their rounds. You really learn something about these people. But I don’t know if the filmmakers working in this style, like Frederick Wiseman (High School, 1969), went in with any particular intention to get something specific from their subjects. What they offer is just a milieu, a bland milieu. It’s kind of horrible. But I’m much more interested in this.

JW: It’s very difficult though, I mean there’s a great question here: one of the things about interviews is that wherever the interview is — even here in your living room with a glass of wine — we’re completely off-duty, we could be doing other things, but there’s always a set-up. I mean the way were talking in the room over there when you were looking for that piece of paper and I was looking for an address on the computer… we moved into a whole different domain and everyone does that.

MK: We’re trying to make sense.

JW: Yeah, well, we’re also professionals and we know what we’re doing; but there’s another level, I think, even if we were amateurs… even if we asked your uncle Ted and my auntie Joan to sit down with a tape recorder in front of them and interview each other, they would switch into another mode that would be a product of the construct.

MK: You switch to public mode. Everyone of these interviews does this.

JW: Exactly. Well, that’s my question, because it’s incredibly difficult to produce a deferment of the set-up that allows people to emerge through their hesitation, or uncertainty …or professional framework… Maybe only time…

MK: It can be reached through time.

JW: And maybe through alcohol and drugs.

MK: But then you also get a certain kind of response.

JW: Right, then you’re hyped up.

MK: Like I could give you a bunch of drugs and I know what I’d get… to a certain degree.

JW: Hey, I’m not sure about that [laughter].

MK: OK, you’d reveal yourself in a certain way, but is that really a portrait of John? No, it’s not, because that’s not how you are twenty-four hours a day. It’s a portrait of you inebriated. This idea of revelation…

JW: The confessional free play of the mind.

MK: I think that’s overplayed, you know.

JW: Which brings me to another thing that’s always interested me, something that we’ve already hedged around in our discussion. As a consequence of the fact that there’s a setup, there’s another thing that always happens in an interview, or most interviews, even with people that know each other, and that’s embarrassment and awkwardness. There’s something a little nervous. There’s something… however it plays out… whether it has to do with the cycle of pathology of your relationship with the other person, whether it’s to do with the context, with the thing you know that’s going to be eventuated in print… there’s always this nervousness and embarrassment… I actually love those moments.

MK: I do too.

JW: And I think they’re really creative… Do you think you can take this a step further in another piece? One part of your current interest in the vernaculars of downtime Americana could take the form of a long piece of writing. I don’t see why not.

MK: Well, that’s related to my interest in anonymous mass culture. What I’d like to do is interview auteurs in various fields. I’ve become very interested in notions of auteurship relative to forms that are not generally thought of as having authors… that are basically invisible. I think it would be very interesting to explore this. For example, I’ve become interested in auteurship in pan and scan.

JW: Pan and scan?

MK: Pan and scan is the refilming of a widescreen film for television. Somebody has to do that. This is not a job one gets recognition for. Yet, there must be a hierarchy of pan and scan directors… people who are known for being good at it… turning a widescreen film into a squareformat film… that’s a form of directorship that’s completely unrecognized.

JW: Don’t machines do this?

MK: No, people do it.

JW: It would be great to interview the people who do that…

MK: …to develop an auteur theory of pan and scan… to interview film directors and ask them who they would choose to pan and scan their films. Who’s good at it? Of course, nobody actually wants their films to be panned and scanned, just like no writer wants their essay chopped in half. But if you have to have somebody do it, constitutes good pan and scan? That interests me. Why do people want films panned and scanned anyway?

JW: That’s the pressure of TV…

MK: The pressure of television, right. The pressure of something that’s completely outside anybody’s desire and yet you have to conform to it. I’m curious about work that’s produced under those kinds of restrictions right now.

JW: When you say you want to interview protagonists involved in filtering forms of cultural invisibility — presumably this would be just one chapter or one installment… and there are other domains that interest you?

MK: I’d try to find a number of things like that.

JW: Did those kinds of situations arise when you were thinking through the extracurricular project?

MK: I don’t know where this came from. I got to thinking about it simply because I was angry that I couldn’t find widescreen versions of films. I could only get the pan and scanned versions. I was always arguing with the manager at the video shop. He didn’t even understand what I was talking about. I tried to explain it to him: “Look… you’re losing close to a third of the film.” But he didn’t understand, he couldn’t see it even when I pointed it out. And I realized that ninety percent of cultural production is like that. Nobody sees it. On TV, for instance, I’m very interested in commercial directors, the people who direct the mundane ads. What is the hierarchy of that? There must be people who direct certain kinds of commercials… like, are there directors who just do drug commercials?

JW: For a while in the 1960s, my father just did medical commercials.

MK: See, so that’s a specialty, and there must be certain conventions of that.

JW: I can see how that fits with one of your art world concerns, because it’s about ritual and it’s about repetition. It’s about professionalism again.

MK: And cultural invisibility.

JW: Yes, about doing something so well you can’t see it’s there.

MK: A quality being hidden.

JW: This is the kind of thing that operates just below the level of the skin; in other words,a circulation system that you can’t quite see because it’s not on the surface…

MK: …because it’s there every day. It can’t be seen. My relationship to media is like a slow-growing tree. It’s taken me some thirty years to recognize auteurship in these omnipresent forms. It only ceased to be invisible to me when I started to work with those forms myself. I realized that there is nothing that’s invisible unless you let it be invisible. And then the question is: culturally, why is it invisible? That’s the big question. Why is it invisible?

JW: Do you think new media has complicated this question by making it schizophrenic? I mean, using the computer in a basic everyday way you encounter this division: on the one hand, an intense reinscription of the individual… the blog, the email, text messaging — all kinds of ciphers of modern day individuality; and then, on the other, you have this massive structural system, the internet itself with all its dependent apparatuses, which are themselves all systems, pure systems operating with an extension we’ve never seen before. So we have this extraordinary separation between one and the other, self and system, and the new compounding of the two in cyber-culture. I think it’s in a different dimension.

MK: Well, the attraction of new media is that it’s novel. It becomes boring as it becomes endemic. That’s happening with blogs already. When everybody has a blog, it will become like any other common form of communication… like letter writing. Who’s a good letter writer? Of all the letters that have ever been written, only a few have been brought to light and examined. The great auteurs of letter writing have probably never been discovered. So, such a thing has to be brought into the world of aesthetics and looked at critically before notions of quality can be established.

JW: Well, but there are two levels of fascination: one would be auteur theory, which is essentially that the letter writer or the blogger is superb within the limitations of the genre. Byron wrote great letters. He was also a reasonably good poet. And you get that many times in the history of literature. But then you have this other level of occasions, in which such and such a person is a great stylist and writes with an eccentric flair, which one could rationalize in literary terms as “excellent”; but what’s interesting in the end is the obsession with their niche. Exactly what you were talking about before, this idea of working, rubbing a surface so intensely that you puncture a death into it just by the friction of repetition, professionalization, perfection, and ritual.

MK: This is why I’m harping on about Jim Shaw. Jim’s problem is that people don’t really see what he does. This is a guy who knows more about the iconography of mass media than anybody I’ve ever met in my life. He knows all the illustrational styles geared toward particular worlds ofproduction. Do people give a shit? No, they just want to see it generically, as garbage culture. That’s not how he sees it. They don’t want to see how Jim Shaw sees it because they don’t want to think about. They are happy with the way things are… as far as pop art goes. With somebody like Jim, because his work is so historically complex, people just want it to go away… to refuse to talk about it in an intellectual manner. They want to dumb it down to their level… the art world’s level of understanding of mass culture. It pisses me off.

JW: Well it’s interesting with Jim because he’s got three modes of address to this knowledge bank. One mode is to appropriate,as in the thrift store paintings which are just “taken” by reproducing and representing them elsewhere; another mode is to dream about popular cultural forms and to produce interesting mediations of these dreams in various media; and there’s another mode still, which would be — the most interesting mode, I think — instinctively to reinvent cultist forms as in Jim’s Oist project. But the art world loves appropriation. Sometimes that’s all they love.

MK: They don’t want to spend the time with work that really takes these omnipresent terms and does something different with them, because then they would have to understand the terms themselves.